Aimé Césaire was born on the 26th of June 1913 into a large family of Basse-Pointe, a town on the North-Eastern coast of Martinique. His father, a civil servant who worked for the tax department, ingrained in him the habit of reading, introducing him to Dumas and other French novelists. Césaire thus became deeply interested in Literature, in French and in Latin from a very early age. Moreover, his teachers at high school were men of colour who thought it their mission to elevate their people to a higher level of culture; it was one of them who encouraged him to continue his studies in France.

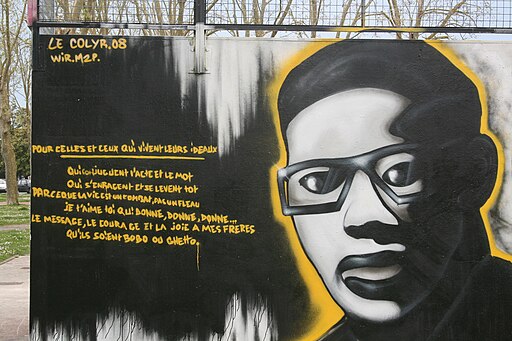

Hommage à Aimé Césaire sur le

Skatepark de Royan.

By Barraki (Own work)

[CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

In 1936 he obtained a government scholarship to study at the Lycée Louis-Le-Grand in Paris. While there that he met Léopold Sédar Senghor, a young Senegalese poet who was later to became the first president of independent Sénégal. At the Lycée and later at the École Normale Supérieure, where they both studied, Senghor revealed to Aimé Césaire the civilization and history of Africa about which the Martinican had only vague premonitions. Césaire thus became aware that his society was a Black civilization transported to another area of the world where it had become gradually debased and alienated. Additionally, the young scholar's awareness of his singularity within French society, his desire to react against racism and the politics of assimilation, and his heightened awareness of being a man of colour - a Negro - and not a descendant of the Gauls, as he had been taught in school, led him to invent the concept of "negritude", an affirmation of the existence of a great Black civilization and a call for the solidarity of Blacks from Africa and the American diaspora.

The term first appeared in L'Étudiant noir, a review founded in Paris by Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor and Birago Diop of Sénégal and Léon Gontran Damas of French Guiana. Césaire employs it again in his first publication (1939) of the Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a return to my native land), a long dramatic and narrative poem which brought him to the notice of the world and which remains to this day his most celebrated work.

Written in a very free form and mixing long streams of feverish prose with segments of rhythmic verse, the Cahier was almost 70 pages long in its final edition. Structurally, the poem involves a series of returns and reversals that to some extent recall one of the major experiences that inspired it: the poet's "exile" in Paris and the shock he felt upon returning to his native island for the first time. The poem's profuse lyricism and the sometimes surrealist billing of its images have sometimes disconcerted the critics. Indeed, understanding the key elements of the Cahier involves exploring it from different directions; however, Negritude is the main point upon which all its perspectives ultimately converge. The reader is also buoyed along by a series of metaphors that relate to the sun and evoke a sort of cosmic birth.

Césaire's long political career, which lasted almost half a century, began in 1945 when he was elected mayor of Fort-de-France and deputy in the French Constituent Assembly on the ticket of the French Communist Party. It was he who in 1946 introduced in parliament the bill which would make the colonies of Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Martinique and Reunion Island departments of France. But alongside his political career, the literary work of Aimé Césaire burgeoned with the publication of several collections of poetry, all bearing the mark of surrealism (Soleil Cou Coupé in 1948, Corps perdu in 1950, Ferrements in 1960). In 1956, he moved towards the theatre. With Et les Chiens se taisaient (And the Dogs Were Silent), a stellar work, said to be impossible to stage, he explored the tragedies involved in the struggle for decolonization by using the Promethean-like figure of the Rebel, a slave who kills his master and is then betrayed by his fellow slaves. By revisiting the Haitian experience in La Tragédie du Roi Christophe (The Tragedy of King Christophe, 1963), he sought to stage the contradictions and insurmountable difficulties that faced newly decolonized countries and their leaders. Une saison au Congo (A Season in the Congo, 1966) presents the tragedy of Patrice Lumumba, the father of independence in the Belgian Congo. Finally, Une tempête (A Tempest, 1969), an adaptation of Shakespeare's The Tempest, explores the question of racial identity and of language in the colonial context as well as the strategies of cultural alienation deployed by European colonial powers.

Aimé Césaire in his lifetime published a large body of work, including collections of poetry, plays and essays. Numerous international seminars and conferences have been organised around his literary work which is now universally known. He died on April 17, 2008 in Fort-de-France, Martinique. On April 6, 2011, the French Republic immortalised the Martinican man of letters by posthumously bestowing on him an honour reserved for France's greatest minds: a monumental fresco and a plaque in the Pantheon. By so doing, the French Republic officially placed Césaire among the ranks of such figures as Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Émile Zola.